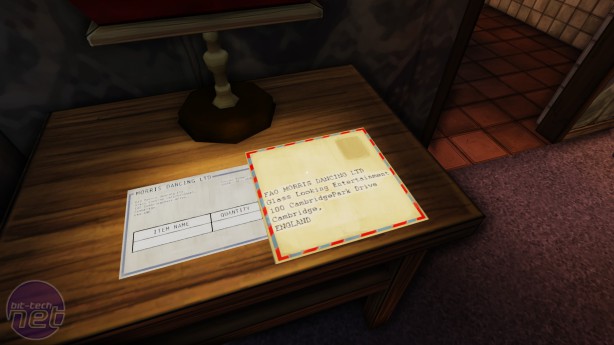

More important than its picturesque nature, however, is the detail with which Ether One's environments have been crafted. There are a wide array of objects to pick up and examine, notes and diaries to read, and other incidental details that help define Pinwheel's solidity as a place. This is especially important with the less idyllic areas such as the mine and the arsenic factory. These areas sport a far more foreboding atmosphere, where workers dissatisfied with low pay, tough work schedules and lax safety policies scheme against the owners, and where the owners fret about profit margins and the threat of buyouts. White Paper Games demonstrates a deft touch when it comes to world-building.

The only disappointment is the distinct lack of life within this world. Ether One is a very lonely game. Your only companion throughout is the disembodied voice of your supervisor, and the occasional ghostly sounds of life in certain areas. This is understandable to an extent, given how difficult and expensive it is to model, animate, voice and write engaging characters. But it's nonetheless a shame that such intricately crafted environments are left so empty and still.

With regards to what playing Ether One involves, White Paper takes the novel approach of offering you a choice in terms of your interaction with the world. Progressing the story is very simple; you collect "memory fragments" in the form of ribbons dotted around each of the four main locations. Each one reveals a little more of the two story threads running through the game, and collecting all of them in one area unlocks the next. This route only requires you to explore each environment thoroughly, and offers a relatively quick path through the game.

At the same time, scattered around Pinwheel are a number of broken "Projectors" that, when assembled, play a reel of film which provide further enlightenment into the events occurring both in Jean's fading memories and the research institute itself. But putting the projectors together requires you to solve some puzzles that don't so much tease your brain as bully it to the point of developing a personality disorder.

The puzzles involve what is arguably Ether One's most interesting mechanic. Pressing "T" will instantly teleport you back to an area known as the Case, a central hub where you can access notes collected during your travels, enter certain plot-specific locations, and most importantly, store items you pick up. Pinwheel is crammed with the artefacts of the everyday, many of which are useless to you, but hidden amongst them are crucial pieces of the game's many puzzles. Ether One combines this with various chalkboards, signs and noticeboards that require you to write down a specific name or number.

This results in some fiendishly difficult puzzles. Too fiendish in fact. Even in its hints Ether One is extremely vague and nebulous. Some of the writing boards can be very easily missed, while occasionally the solutions to the puzzles lie outside the game, which it fails to make clear. Compared to Portal, which had a knack for making the player feel clever, Ether One too often makes you feel stupid.

The decision to offer the player the choice of progression paths is a respectable one, but the problem is one is very easy and not particularly satisfying, while the other is extremely gratifying but also incredibly hard. The ideal approach would have been down the middle road, making the puzzles a necessity, but slightly less obscure.

Still, this approach isn't entirely without merit. Being able to walk away from a particularly exasperating puzzle and still enjoy the rich environments and multilayered story White Paper has created has its advantages. Ether One is a charming, clever and compelling little first-person adventure. It's just a shame that its artistic and systemic halves are unable to coalesce.

The only disappointment is the distinct lack of life within this world. Ether One is a very lonely game. Your only companion throughout is the disembodied voice of your supervisor, and the occasional ghostly sounds of life in certain areas. This is understandable to an extent, given how difficult and expensive it is to model, animate, voice and write engaging characters. But it's nonetheless a shame that such intricately crafted environments are left so empty and still.

With regards to what playing Ether One involves, White Paper takes the novel approach of offering you a choice in terms of your interaction with the world. Progressing the story is very simple; you collect "memory fragments" in the form of ribbons dotted around each of the four main locations. Each one reveals a little more of the two story threads running through the game, and collecting all of them in one area unlocks the next. This route only requires you to explore each environment thoroughly, and offers a relatively quick path through the game.

At the same time, scattered around Pinwheel are a number of broken "Projectors" that, when assembled, play a reel of film which provide further enlightenment into the events occurring both in Jean's fading memories and the research institute itself. But putting the projectors together requires you to solve some puzzles that don't so much tease your brain as bully it to the point of developing a personality disorder.

The puzzles involve what is arguably Ether One's most interesting mechanic. Pressing "T" will instantly teleport you back to an area known as the Case, a central hub where you can access notes collected during your travels, enter certain plot-specific locations, and most importantly, store items you pick up. Pinwheel is crammed with the artefacts of the everyday, many of which are useless to you, but hidden amongst them are crucial pieces of the game's many puzzles. Ether One combines this with various chalkboards, signs and noticeboards that require you to write down a specific name or number.

This results in some fiendishly difficult puzzles. Too fiendish in fact. Even in its hints Ether One is extremely vague and nebulous. Some of the writing boards can be very easily missed, while occasionally the solutions to the puzzles lie outside the game, which it fails to make clear. Compared to Portal, which had a knack for making the player feel clever, Ether One too often makes you feel stupid.

The decision to offer the player the choice of progression paths is a respectable one, but the problem is one is very easy and not particularly satisfying, while the other is extremely gratifying but also incredibly hard. The ideal approach would have been down the middle road, making the puzzles a necessity, but slightly less obscure.

Still, this approach isn't entirely without merit. Being able to walk away from a particularly exasperating puzzle and still enjoy the rich environments and multilayered story White Paper has created has its advantages. Ether One is a charming, clever and compelling little first-person adventure. It's just a shame that its artistic and systemic halves are unable to coalesce.

-

Overall75 / 100

MSI MPG Velox 100R Chassis Review

October 14 2021 | 15:04

Want to comment? Please log in.